FILM CREW CREATES ARCHETYPAL IMAGE OF 1790s QUEBEC SEIGNEURIE BUILT FROM SCRATCH

The Gazette, Montreal, Saturday 7 September 1996

Peter Lanken Special to the Gazette

Quebec, 1759: Maj.-Gen. James Wolfe spends his summer shooting cannonballs across the river at Quebec City. He also burns villages and farms up and down the St. Lawrence River, just as he learned to do in Scotland a dozen years before. In September, he wins his last battle and dies on the Plains of Abraham.

Montreal, 1760: 11,000 English soldiers arrive at Lachine, having travelled from Albany, N. Y., by way of Lake Ontario, in the most astounding military journey of the age. Thousands more arrive from Lake Champlain and from Quebec.

The remnants of the French army, outnumbered 5 to 1, surrender the city, and, with it, Canada.

Quebec is in English hands but in trouble. The capital is ruined, the currency is worthless, people are starving. The financial adventurers who always attend the destruction of a civilization arrive in number.

But the civilization of French Canada, unlike that of Scotland, isn’t destroyed. As we now know full well, the French language and the Roman Catholic religion are retained and protected.

A bunch of bureaucrats and minor aristocrats leave, but most of the administrative apparatus of Quebec remains in place.

London, tired of throwing money up the St. Lawrence and already worried by English-language sedition just to the south, doesn’t want any extra problems in North America. A difficult peace ensues.

Montreal,1995: Cité Amérique, a local film company, begins work on an 11-part television series about that troubled period of Quebec history. The series will tell the story of Marguerite Volant, a fiery young woman determined to save her father’s seigneurie near Quebec City.

The Cité Amérique team are well known. They have already made the award-winning film Eldorado and the television series Blanche and les Filles de Caleb. (Both these series were watched by more than 3 million viewers in Quebec.) Charles Binamé will direct Marguerite Volant; Catherine Sénart will star. Like Cité Amérique’s other productions, Marguerite will be seen around the world.

The producers wanted the film to accurate represent the Quebec of the 1760s. they consulted with historians, including Conrad Graham of the McCord Museum. “They’re really doing a super-duper job of historical re-creation,” Graham said. ”For instance, no plates or cups survive from that time, but we did find some potsherds during excavations at Place Royale. The film people actually had new items made by a ceramist, copying the shapes and glazes exactly from those broken bits.”

They decided to build an 18th-century seigneurie north of Trois-Rivières, and called on Montreal architect James Fox to prepare the designs. Although he is a graceful and knowledgeable draftsman, Fox knew that he was no expert on early Quebec architecture.

“I thought of it as an opportunity to learn the architecture of another time, a high-pressure graduate course in architectural history,” Fox said. “I talked to the guys at the McCord, and I visited La Ferme St-Gabriel and the restored windmill at Ile-Perrot. I spent a couple of weeks studying the drawings at the Ramsay Traquair Archive at McGill. I started drawing right away, and just drew and studied and drew some more, until my sketches started to look right.”

Parenthetically, he added, “I was very impressed by the quality of work done by Professor Traquair and his students during the 1920s and 1930s.” (these were measured drawings of old architecture, in ink on linen, showing all construction and decorative details; some of the best can be found in Traquair’s 1947 volume The Old Architecture of Québec.)

Fox continued: “But you can see the draftsmanship begin to decline in the 1930s and almost disappear by the ‘50s. I’m sure it’s no coincidence that the deterioration parallels the rise of Modern architecture in Canada.”

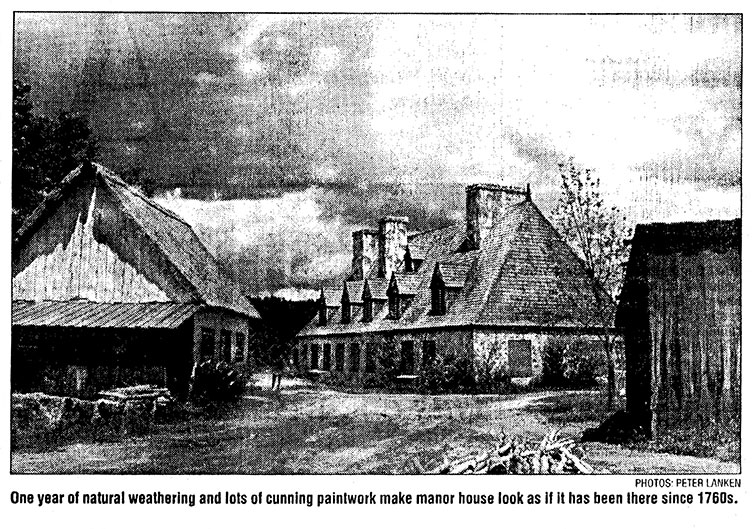

We visited the new seigneurie at the height of summer. Clouds towered and tumbled, and the rain of previous weeks had turned the hills and fields intensely green. The manor house is grand, 92 feet by 32, thick stone walls, steep hipped shingle roof, with two rows of little dormers. It is reminiscent of the old photographs you’ve seen, or the paintings of Marc-Aurèle Fortin, or the superb houses you’ve passed in your travels through Quebec. Its age is indeterminate – a year of natural weather and a lot of cunning paintwork make it look like it’s always been there. Quebec’s ferocious ecology has scattered wildflowers up to its front door. But knock on the stone wall and it sounds hollow.

“Building for film liberates you from a lot of the everyday practicalities of real construction,” Fox said. “This house isn’t really a stone house. Those walls are made of 2 inches of stone and mortar on construction board and 2-by-4s, then 3 feet of empty space, and plaster and paint on the inside. The whole thing rests on 2-by-10s flat on the ground.”

Not far away is the seigneurial windmill, a little masonry cylinder with sails and a conical roof. “It isn’t real, of course,” Fox said. “The sails are turned by a big electric motor inside. In fact, we got the pulleys wrong, and when we first started it up, those sails were whanging around so fast that the whole building almost took off and flew into the river.”

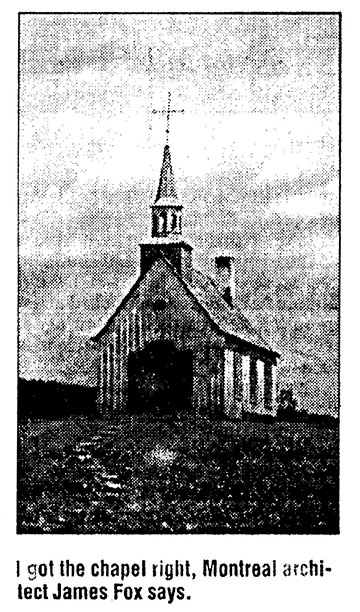

The land slopes away, over to a little hill with a perfect little chapel at its summit. “That was fun,” said the designer. “I think I got in nearly right…. At the first press visit, I had candles and incense burning inside, and just as the crowd started up the hill, I began to ring the bell. A lot of the visitors crossed themselves and the local priest congratulated me.”

The story requires and Indian trading post in the bush. Fox laughed. “It was just like boys playing forts in the woods, a boyhood dream. I got to go into the bush, pick a site where the river tumbles over big rocks, and mark the trees to be cut. In a few days, this little log house was finished, complete with lodges for the Indians.”

Then there’s a real forge, with furnace and anvil, and a few smaller houses, and barns, and shelters for pigs, and chicken houses and a duck pond. It was all built in less than eight weeks, including the access road and electrical service.

The architect showed me a photograph of 55 of the people who did the construction work, some of them film specialists from Montreal, some local craftsmen. You can see the pride in their eyes, the sense of accomplishment.

Think of it: in a remarkable short period of time and under great pressure they’ve created a concentrated memory, an archetypal image of Quebec that will be seen around the world. How many recent buildings can be said to be really representative of this unique land? All those people have a right to be proud.

The first episode of Marguerite Volant will be shown on Radio-Canada Sept. 26. An introductory program, Il y a Longtemps Que. will be aired Sept. 25. A related exhibition, also called Marguerite Volant and curated by Conrad Graham, will open at the McCord Museum Nov. 15. Costumes, furniture and other artifacts from the 18th century and from the film will be on view. Drawings by Ramsay Traquair and James Fox will be featured.

Peter Lanken is a Montreal architect.