BACK TO THE FUTURE

The Gazette, Montreal, Saturday, June 17, 1995

Architecture centre mounts an ambitious exhibition of visionary images

PETER LANKEN, SPECIAL TO THE GAZETTE

Hey, boys and girls, let me tell you what the world was like when I was your age. No, I’m not going to tell you how I had to walk nine miles to school through 10-foot snowdrifts, or how I had to work in the fields from an early age.

No, I want to tell you that the world was once a bigger place, with another dimension, another realm that no longer exists. The world used to contain a future.

It’s hard to talk about the futures of past times now, when it’s hard to see any future at all. Or any future worth striving for. It’s even harder because those past futures constantly shifted shape, slipped from place to place and slid in and out of focus. They multiplied and divided, and their offspring often appeared far from home.

But now, a bunch of historical futures has been assembled in a major exhibition at the Canadian Centre for Architecture. A French professor of architectural history, Jean-Louis Cohen, has put together a spectacular group of drawings and artifacts to show us North Americans how North America determined the shape of European futures during the last 100 years.

It is not an exhibition of Popular Mechanics airplanes you can park in your garage or space ships to take us all to Mars. It concentrates, not surprisingly in view of the venue, on architecture and the city, on how architects saw then how we would live now.

To set the scene, the anteroom of the exhibition contains a group of traditional, oversize water color drawings from the École des Beaux-Arts art Paris from about 100 years ago. “Look at the size of those buildings,” said Jean-Louis Cohen. Everything connected with America was be definition BIG.”

And America continued to expand, in reality as well as in the European imagination. City growth, coal production, steam generation, all were outstripping comparable European figures. New York was humming loud enough to be heard in Europe, louder even than London hummed at the centre of her empire.

In 1893, Chicago held its great world’s fair, titled The Century of Progress. Under the influence of what Henry Adams called “trader’s taste,” it turned to architects trained at the École des Beaux-Arts to build a classical “white city” on the shores of Lake Michigan. Louis Sullivan claimed this delayed the future by half a century. Europeans, on the other hand, already fascinated with America, came to look at their old culture transplanted, painted white, and called Progress. In passing, they saw New York; at Chicago, they looked behind the exposition and saw an astounding explosion of activity, vigor, confusion, squalor and profit.

They saw the railways, the meat-packing plants, the skyscrapers, the factories and the grain elevators. The saw the future firsthand, and they fell for it.

As in any intense relationship, their attraction contained large components of both desire and fear. They went back to Europe and tried to wrap their minds around what they had seen, tried to apply theories and codes to it.

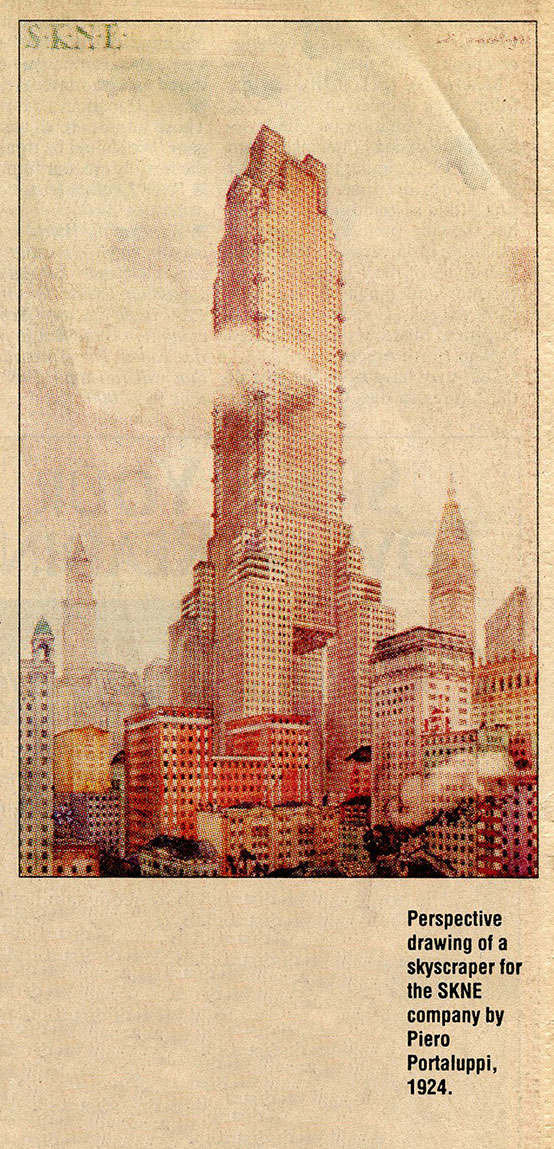

By the 1920s, north America was building the future. Great architects – Bertram Goodhue, Raymond Hood, Montreal’s Ernest Cormier – were building the Nebraska State capitol, Rockefeller Centre, the Université de Montréal.

But even while these buildings were under construction, they were too old fashioned for the Europeans, who saw in them too much theatre and not enough theory.

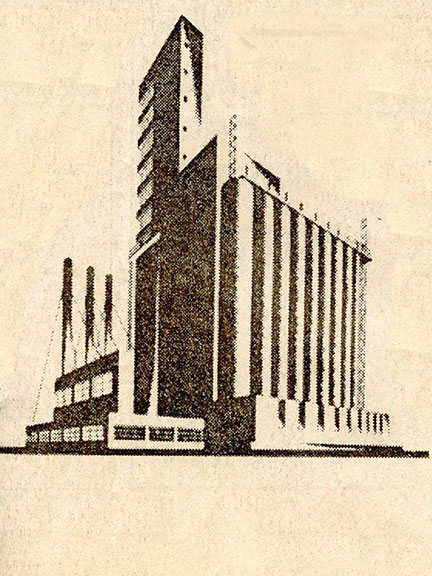

In Europe they had turned their interest to the industrial buildings they had seen in Chicago. Here were structures that were free of tradition, that were based on pure theory. So they prepared beautiful perspective drawings of factories and grain elevators and constructed a theoretical future around them.

Mies van der Rohe discarded the pinnacles and theatrics of New York, and in 1921 drew his famous, flat-topped glass skyscraper for Berlin. These drawings – the originals, depicted in every history of modern architecture – are here at the CCA.

Walter Gropius build the Bauhaus at Dessau in 1925, but for a school it looks a lot like a factory; in fact, like his Fagus factory of 1910. Again, the original drawing is here.

Le Corbusier mistrusted New York more than anyone, Having failed to persuade either Citroën or Peugeot, he finally got Gabriel Voisin, also a car manufacturer, to underwrite his 1925 design for the complete rebuilding of Paris. His 18 Cartesian, cruciform towers wiped out half the city in a move “directed against the purely formalist and romantic conceptions of the American skyscraper.” (By the way, there are two Voisin automobiles currently on view at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. I had never seen one before. You can see them and Le Corbusier’s images in the same day.)

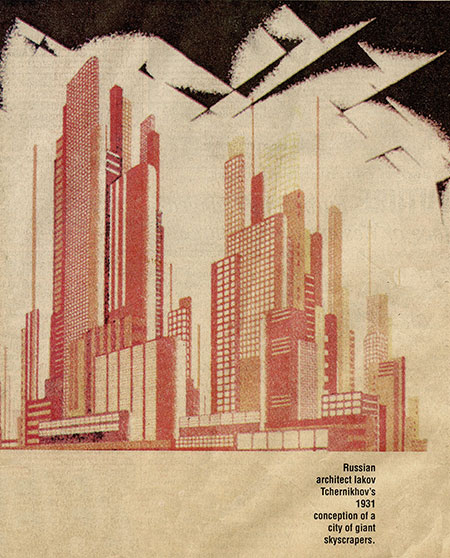

The Russians, on the other hand, bought into the American future directly. Albert Kahn, the architect of the Ford factory at River Rouge near Detroit, and his brother Moritz built more that 500 industrial plants in Russia between 1929 and 1932 as part of Stalin’s first Five Year Plan. Russian architects couldn’t be left behind: they create their own future, vaguely based on those factories and called it Constructivism. You can see some of their drawings not far from Albert Kahn’s construction layouts.

Then came the 1930s, and the world changed. Stalin shut down Russia with his Great purge. The Depression shut down the American building industry. The Nazis shut down the Bauhaus – Goebbels called it “an incubator of cultural Bolshevism” – and had a real Aryan roof built on top of it, to fit with his new (non-American) future. Gropius and Mies both came to the United States, where their old futures had been born.

There they took over the schools: Gropius at Harvard, Mie van der Rohe at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago. There they inculcated a generation of students with their visions. The architectural finesse that Goodhue and Hood had struggled with was forgotten. The future of American architecture became European. When construction resumed in the l950s, building owners all over exclaimed with delight, “You mean I don’t have to pay for all those columns and capitals any more?”

Meanwhile, back in Russia, the future took another unlikely twist. The CCA exhibition includes a series of Russian drawings from around 1950, similar to those older Beaux-Arts drawings in size and finish (that is, grand and powerful), but showing projects for gigantic buildings for Moscow in the American styles of the 1920s. There are columns and pinnacles and New York setbacks. Constructivism was forgotten: Moscow’s future moved back to North America.

That may have been the first of the futures to die. We don’t now think of Moscow as a city of glittering American skyscrapers.

Here, in North America, the future – that confident system of belief that underlay the whole Modern Movement – also began to die. Maybe in the 1970s: Star Wars showed a future based on a medieval past; road Warrior and Blade Runner re-introduced us to the dark, scary side of the city that the Europeans had seen in Chicago in 1893.

Here in Montreal, the federal government demolished Grain Elevators 1 and 2, to replace them with a vacuous suburban green space. Those elevators, once admired by le Corbusier and used as examples by him are so completely demolished that they don’t even appear on souvenir T-shirts. Even Jean-Louis Cohen, putting this exhibition together for Montreal, has forgotten them.

The future that the elevators once represented – the Modern Movement – has now been recycled so many times that it is old-fashioned. The recent competition for the new Outremont Library (ably reviewed here a couple of weeks ago) showed this. Those projects all wrestled with the now-empty questions of Modernism: what do you do with a plain box? How do you turn a 1910 German factory or a 1927 French villa into a 1995 Montreal library?

The CCA should be congratulated for putting all these futures in a museum, where they belong, and where they can be studied and admired as we admire, say, 18th-century Canadian fortifications. Those futures are all past now and gone. We should be thinking about the next future, our future.

Peter Lanken is a Montreal architect.

Scenes of the World to Come: European Architecture and the American Challenge continues at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, 1920 Baile St., until Sept. 24. The exhibition is the first in a five-part series called The American Century that will run until 1998. Information: 939-7000.