THE KNOT AT THE QUEBEC PRISON

Peter Lanken architecte

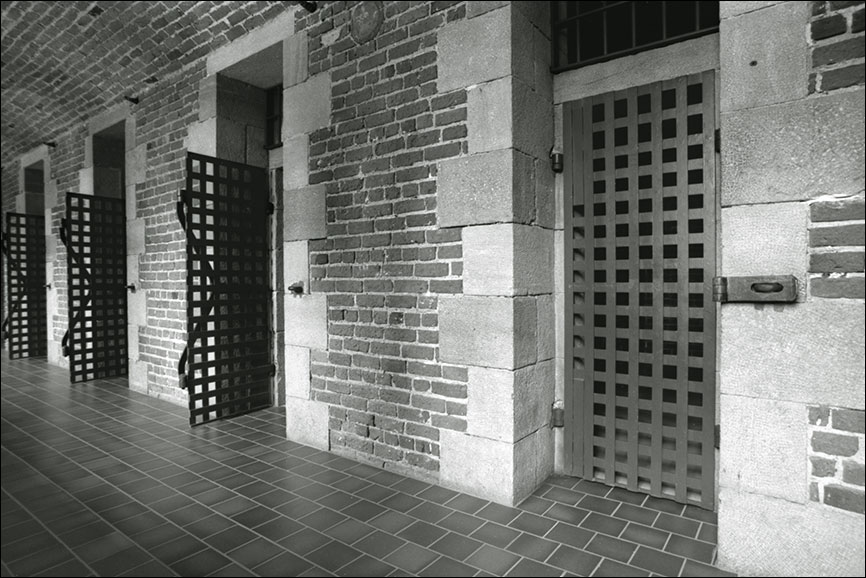

In THE EAR at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, I wrote: “In 1989, we [artist Betty Goodwin and myself] were invited to compete for another work of art, this time in Quebec City, where the Musée des beaux-arts was expanding into the old Prison de Québec. We took an early morning train and were given the full tour of the project, then on the very early stages of construction. I was disturbed: the project was wrong. They were trying to transform a prison into an art gallery, but they were keeping the cells, the iron doors, the very instruments of incarceration. The usual smells of a construction site, sawdust and tobacco, and plaster, paint and piss, were mixed with the odour of ancient anger and despair. Every brick breathed a century of sighs. The discord dangled deep in the soul.

“I thought, ‘Evil and Art cannot live in the same building,’ and tried to explain this to Betty. She simply said, ‘Yes,’ and continued to gaze, deep in thought.”

The work was to be located in a little octagonal tower that surmounted the prison. It was remote from major circulation: it had to be a destination. More, it had to acknowledge the discomfort we had both felt.

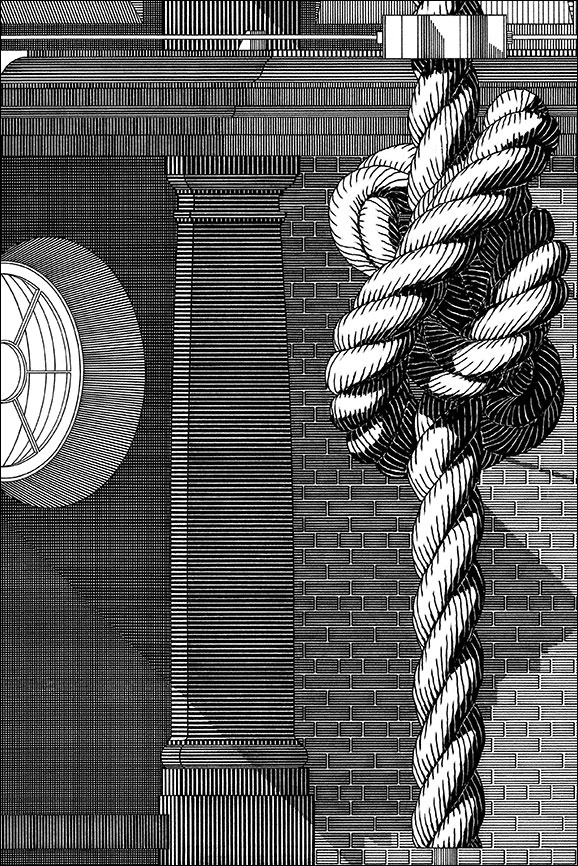

Once again, Betty and I spent hours, days, talking, trying to understand our profound disquiet. This was her territory. This was where she lived and worked, trying to resolve, to represent, the pervasive discord that hovers over all our lives. She wandered in her studio, searching always to connect the words and objects spread on her big work tables. From deep in her memory she drew an old idea: “The knot in which the soul is bound,” and joined it to a knotted rope which she had once had cast in bronze.

The concept – the phrase and the bronze knot – had power: it rolled over the deformity we had both seen, enveloped it, and would enfold the beholder.

The setting now became my problem. The tower in which the work was to be erected was nearly a ruin: unglazed, unroofed, unfinished. During days of sketching, I pulled out every architectural figure I knew. It became clear that modern architecture, even the most formal landmarks of recent design, was powerless in this situation. We had to go deeper into our common traditions, back to classical design, and then further, to the most severe, the most archaic of the orders: the Tuscan. Unadorned and solemn, this order could prevail against the malign atmosphere of the place.

The visitor’s first view of the knot was from below, as he mounted a narrow steel stair through the stone floor. Once inside the little chamber, surrounded by the power of Tuscan pilasters rising two storeys, he would see the knot just above him. And the rope, floating over the floor and reflected from below in a stainless mirror. The device, “Le noeud dans lequel l’âme est liée” was to be spelled out in stainless letters let into the limestone floor around the mirror. At dusk, relief was offered by the lights of the city spread below.

We made a quick model and presented it. It was rejected. But the idea, the design, had enduring value, and I undertook a big (one-twelfth scale) formal ink drawing, on which I worked, intermittently, for several years.

March 2018